If You Knew Suze

'The new generation causing all the fuss was not driven by the market; we had something to say, not something to sell.' Suze Rotolo, A Freewheelin’ Time, 2008

Without hat or gloves, their shoulders hunched against the cold, they walk up the middle of Great Jones Street through dirty snow, his bare hands tucked into the pockets of his jeans while her arms circle round his right arm, holding it tight. He leads the way, slightly ahead of her, his head tilted towards her, and she, being a little shorter, leans her head on his shoulder. Their legs march in step, with their left feet suspended in mid-action, pointing up and forward, ready to strike down with their heels, their image frozen for eternity in the sort of transitional gesture that sculptors favor.

He seems lost in thought. Maybe his teeth chatter from the cold, but, clearly, he is not unhappy. She smiles. “She had a smile that could light up a street full of people,” he wrote about her years later in his memoirs.

Looking at the photograph of Bob Dylan and Suze Rotolo in Greenwich Village in 1963, the cover of Dylan’s second album, you can see that they were young and very much in love. You can imagine how cold it was the day that Columbia Records staff photographer, Don Hunstein, shot the image. It nearly makes you shiver, except that Suze’s smile warms you.

Thirty years after the iconic photo was taken, Stephanie Connell, a retired artist, brought a woman named Susan Rotolo to Spring Studio. Susan didn’t want to draw the figure with the rest of us. She asked if she could instead draw the bones in my bone collection. She sat to the side of the room all by herself in the midst of animal and human bones that were to be the most recent subject of her ongoing project. She planned to sew her drawings together by hand to make small art books, inserting an occasional found object.

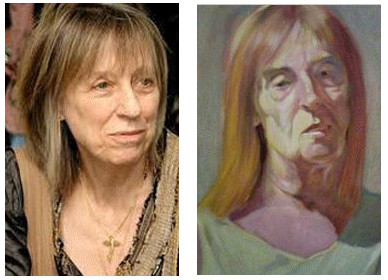

She worked quietly and diligently. When she smiled, her eyes expressed genuine sincerity. She no longer looked much like the girl in the photo. Her face was thinner than it had been thirty years earlier. She was a little long in the tooth, but attractively so. At first glance, she looked like my sister Alexandra, with the same average height and slender build, and the same fair, honey-haired complexion, so much so, that artists would walk up to her at opening receptions and ask her, “Aren’t you Minerva’s sister?”

I imagine that our families could only be related by blood through redheaded Normans, some of whom conquered England in 1066 and others of whom passed through southern Italy as crusading knights and liked what they saw, so decided to take it over.

|

| A photo of Suze, left and a detail of a painting I did of my sister Alexandra, right. There is a resemblance especially in the hair |

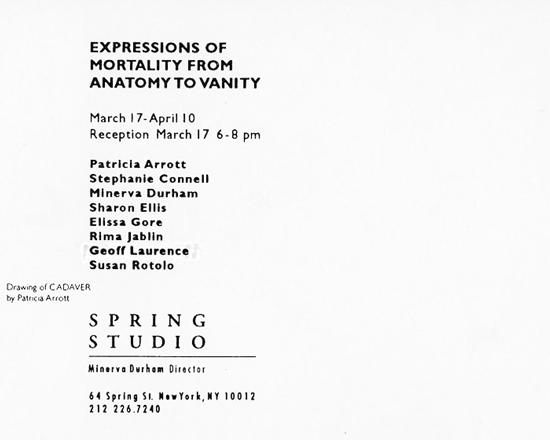

I planned an exhibition at Spring Studio of mementos mori, to be shown in March, 1996. I called it “Expressions of Mortality from Anatomy to Vanity.” Susan was eager to show her hand-stitched books. She joined seven artists who drew the figure at the studio and who also drew bones, dealt with the theme of death, or illustrated medical subjects. All told, the show featured eight artists. Patricia Arrott, Stephanie Connell, Sharon Ellis, Elissa Gore, Rima Jablin, Geoffrey Laurence, Susan and me. Here is the Invitation designed by Haggai Shamir:

|

Such was the power of Don Hunstein’s photo on Dylan’s album cover that people kept asking me during the exhibition if the artist in the show listed as Susan Rotolo was Bob Dylan’s girlfriend. “The record cover,” they would exclaim, “you know, the record cover!” They wanted to know all about her, but I knew almost nothing except that she was devoted to making her art, had been Bob Dylan’s girlfriend for a few years, was married to someone else, and had a teenage son. Apparently she was famous among Dylan fans as his mysterious first love. 'Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right'; 'Tomorrow Is a Long Time'; and 'Boots of Spanish Leather' were written for and about her.

|

| Bone Portraits: Still Lives, last of six versions,Susan Rotolo, 1995, 4“ x 3.75” |

Until I read about her in David Hajdu’s book, Positively 4th Street, I had no idea that the woman named Susan had been a significant person in Bob Dylan’s musical development. Hajdu revealed her to be of good character and deep sensitivity with plenty of human vulnerability, devoted to the cause of human justice.

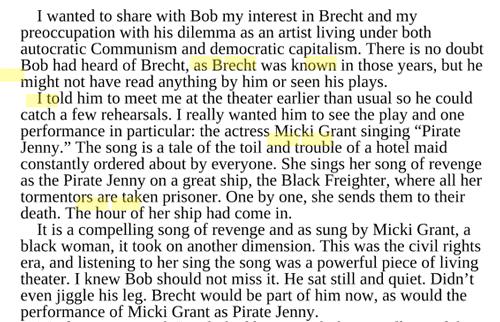

It is commonly agreed that she had a strong influence in Dylan’s early songs, deepening his interest in and understanding of French symbolist poets, English-language folk ballads, American protest music, and the lyrics of Berthold Brecht, In her memoir (published in 2008), Susan describes Dylan’s response to the performance of Pirate Jenny by Micki Grant, an African-American soprano, actress, writer and composer.

|

In 1997 Susan exhibited her handmade books at the Jefferson Market New York Public Library. The show was listed in the Regional section of the New York Times, PLAYING IN THE NEIGHBORHOOD, ALSO AROUND TOWN, on October 26, 1997.

BOOK TO ART — ''The Book as Art,'' an exhibition by Susan Rotolo, displays books decorated by the artist, including a memoir of the 1960's when Ms. Rotolo, who dated Bob Dylan at the time, came of age; Monday-Friday during library hours; Jefferson Market New York Public Library; 425 Avenue of the Americas, at 10th Street; free; (212) 591-0519.

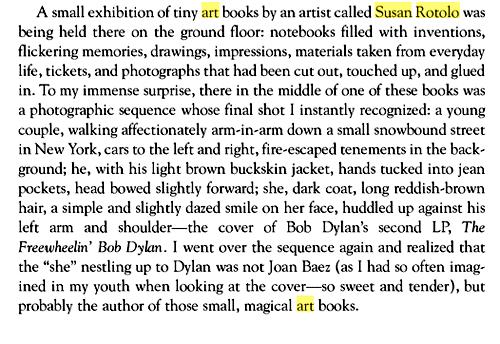

While checking out the architecture of the Jefferson Market Library, designed by Frederick Clarke Withers, Mario Maffi saw the show. He wrote about Susan’s “small, magical art books” in New York City, An Outsider’s Inside View (published in 2004.)

|

|

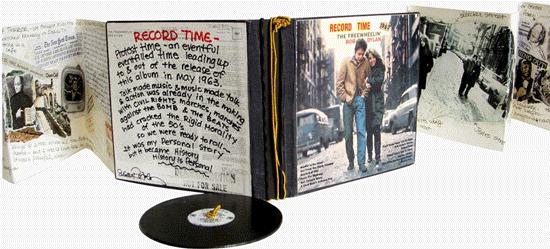

| Record Time - Personal History, artists’ book, Susan Rotolo, 1995, 4 x 4 inches closed, 4 x 50 inches; open: “A memoir of a special time in the 1960’s, concerning events before and after the release of The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan album with both of us on the cover. It’s about the music, the marches, and coming of age, and how those elements, fused together, created a politically active generation.” |

RECORD TIME-

Protest time - an eventful

eventfilled time leading up

to & out of the release of

this album in May 1963.

Talk made music and music made talk,

& action was already in the making

with CIVIL RIGHTS marches, marches

against the BOMB & the BEATS

had cracked the Rigid Morality

of the 50’s

so we were ready to roll-

It was my Personal Story

but it became History

History is Personal

Susan Rotolo

Maffi continues:

|

So, in 1997 Susan Rotolo was coming out of hiding, presenting her story to a small, random audience, telling it in her own way, in unassuming non-commercial, small handmade artists’ books.

It was a start.

In her prose poem, RECORD TIME, she places her relationship with Dylan in its historic context of the civil rights struggle, the anti-war movement and the sexual revolution, just before the rise of second-wave feminism. She scrawls “action was already in the making . . . so we were ready to roll,” alerting us to her nascent feminism. Like many American women at the time, Susan was empowered by participating in protest marches. A newfound consciousness allowed her to reject the sort of relationship that she had with Dylan.

|

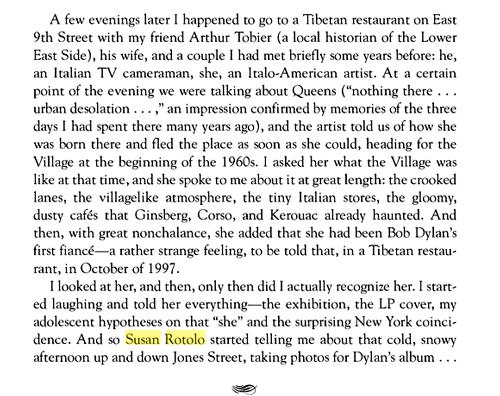

| A Good Old Book, Susan Rotolo, 1998, 9” x 7.5“ x 1.25” closed |

Susan’s phrase, “History is Personal.” plays on the Feminist slogans, “The personal is political,” and, “The private is political,” which were popularized in the late 60’s, when there was a growing consciousness that the personal decisions made by individual women were of great import to American society as a whole and that the society needed to change. Having the vote was no longer enough for feminists, they wanted equal rights and equal pay, as well as control over their own bodies. Customs and laws would have to change to accommodate the health, education, and welfare of all women.

Suze used the name Susan Rotolo in relation to her book production and her personal social life for many years. In the online photo below she is identified as Susan Rotolo with her husband Enzo Bartoccioli at a party for Chico Hamilton in 2002:

|

| Susan Rotolo, Enzo Bartoccioli, Chico Hamilton in 2002 |

Not everyone in New York was impressed with Suze’s connection to past glories or with the mystique of the silent former girlfriend of the famous musician/poet. New residents moving into her apartment building complained that her teenage son Luca sometimes played his guitar in the lobby of the building. Their complaints irked her, but she saw the humor in the situation. Everything was moving upscale, becoming flat and anonymous. She hadn’t wanted to be a legend anyway.

During the years that Suze refused to give interviews to the media, she held close whatever resentment or pain she had. What was there to say? Maybe she talked about the past with Stephanie who was a big sister/mother figure for her.

Stephanie was nonchalantly sophisticated and great fun to be with, a part of the generation of arty young women who lived in Greenwich Village in the 40’s and 50’s that included Virginia Admiral, Julia Ann Crawford, Ruth Herschberger, Alene Lee, Marjorie McKee, Elizabeth Pollet, Dachine Rainer, Edith Stephan, Helen Walker, and Elaine Williams. These women spoke their minds, had brushes with fame, had some success publishing, lived bohemian lives, married famous men and/or gave birth to sons who became famous. By the time I met most of these women through Virginia Admiral, they were minor legends. You might find yourself reading about them in Anais Nin’s memoirs, if nowhere else.

Susan met Stephanie while standing in line at the MOMA for free admission on a cold winter day. They struck up a conversation and were deep into it when a guard interrupted them.

“I can’t let Bob Dylan’s girlfriend stand out here in the cold,” he said to Suze. “Come with me into the museum now.”

“Only if my friend can come, too,” Suze said. They became fast friends until Stephanie died in 2008.

With the publication of Dylan’s memoirs, Chronicles: Volume One, in 2004, Suze’s resistance to notoriety softened. She appreciated his description of her when he met her, calling it “wonderful, generous” in an interview. She was “the most erotic thing I’d ever seen,” he wrote.

She broke her silence. She agreed to be interviewed for Martin Scorcese’s documentary, “No Direction Home,” 2005, which covers Dylan’s career between the years 1961 to 1966.

As luck would have it, Scorcese’s cameraman was sick on the day that Suze was scheduled to be interviewed. My friend and neighbor Lisa Rinzler was called in at the last minute to shoot the interview in Suze’s home. Small talk revealed that Suze had a connection to Spring Studio. Lisa was surprised. She called me and we three made a lunch date. Suze, still essentially a private person, was warm, gentle, and intelligent, as usual.

We at Spring Studio who were friends with Suze somehow knew that Dylan had never lost touch with her. Stephanie must have told us, because Suze never spoke his name. We invented a sort of myth about her first love, and it served us until she finally wrote her memoirs in 2008 and revealed her truths. It pleased us to think that the relationship had ended because Dylan sought fame and abandoned her for Joan Baez who furthered his career.

We were wrong. Suze felt “like a string” on Dylan’s guitar; her mother and older sister disliked Dylan intensely; feminism was on the rise. She needed to be herself.

Then, there was the abortion.

In the early 60’s abortion was not legal in New York State yet, or anywhere else in the country. Contraception was difficult. Neither early withdrawal nor the rhythm method was fail-proof. The birth control pill had just been introduced, but it was not safe, causing death by blood clot in a small percentage of the women who took it. Intrauterine devices were still being perfected. Barrier methods sometimes fail, even today. Most won’t work unless used properly, accompanied by spermicide. Condoms? You couldn’t always find a condom when you needed one, and they sometimes broke.

Many doctors terminated unwanted pregnancies for privileged women, often for married women who already had children, whose mental or physical health, they maintained, would be hurt by a pregnancy. Gynecologists “scraped out” the lining and contents of a woman’s uterus, performing a common surgical procedure called dilatation and curettage which was routinely used for many gynecological problems other than abortions.

First the cervix of the womb was dilated, then a piece of metal with a handle on one end and a blade on the other, a curette, was inserted into the uterus to remove its contents. Ideally, the “D&C” was done during the first trimester of pregnancy. If there was time, the woman was anesthetized, but illegal abortions were often quick and painful.

In 1958 two Chinese doctors developed a method to suction out the contents of the uterus. By the time that pioneering Canadian doctor, Henry Morgentaler, published a “Report on 5,641 outpatient abortions by vacuum suction curettage” (1973), American doctors were already successfully using “vacuum aspiration.” There was not one death among Morgantaler‘s 5,641 women, and the complication rate was only 0.48%. Because suction is safer than scraping, it has become the method of choice for abortions all over the world.

At the time that Suze got pregnant, most sexually active American women lived in constant fear of getting pregnant. While poor women notoriously tried to self abort at great risk to their health, unmarried, pregnant, middle-class white women had a few choices, none of them good.

It was considered best to get a man to marry you fast, preferably the father of the child, but then you were stuck somewhere you hadn’t planned to be and probably didn’t want to be.

It was considered acceptable to take a long vacation, the length of the pregnancy, and to give up the newborn infant. Thousands of loving, financially secure, infertile white couples were waiting for unwanted white babies. But then you had to forever lie about your past while secretly yearning to connect with the child you had abandoned.

Worse, with great difficulty, you could keep the baby, live in shame, publicly disapproved of by all the “happy” married parents who might secretly envy you. Being a single parent with total responsibility, you had to earn a living in a society that discriminated against women, while you constantly worried about the quality of childcare your baby was getting when you were at work.

An abortion, usually expensive, quick and painful, was considered the worst solution of all, an act to be ashamed of, a crime against the state, and a sin against divine powers.

|

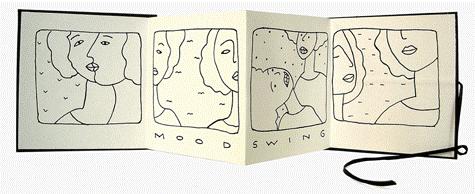

| Short Stories: Mood Swing, print on accordion book, Susan Rotolo, 1993, 2“ x 2” |

Every woman from the sixties has an unwanted-pregnancy story to tell, hers or her sister’s or her best friend’s, each story unhappy in its own way.

Well, you can read about Suze’s abortion in her own words in this excerpt from her memoir, A Freewheelin’ Time: A Memoir of Greenwich Village in the Sixties, published in 2008.

|

|

|

Everything moved quickly after Suze’s book came out. She did interviews and made appearances and was written about favorably. You can see from the excerpts that I include here that she was an excellent writer, honest and empathetic.

A spoken interview with Terry Gross of Fresh Air can

still be heard on NPR. Click LISTEN on “books”

Suze Rotolo: Of Dylan, New York and Art, May 14, 2008:

http://www.npr.org/books/authors/137910356/suze-rotolo

Robert Williams of The Guardian, wrote an insightful piece: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2008/aug/16/biography.bobdylan

|

| Suze about the time that her memoir came out. |

After Stephanie Connell died in 2008, the same year that Suze’s memoir came out, another of Stephanie’s friends, Eileen Krest, planned to mount a memorial show of Stephanie’s works at Spring Studio to be presented in 2010 with the help of Stephanie’s boyfriend Ron Efron and her son Eric Connell.

I ran into Suze and Enzo on the street. “I haven’t read your book yet, but I want to,” I confessed.

She smiled her beautiful, warm smile “Do,” she encouraged me. I told her that Eileen and I were working with Ron, doing a memorial show of Stephanie’s drawings and paintings. Suze was excited and offered to help.

But as the show neared we couldn’t reach her. Finally, I got a note from Eileen:

December 3, 2010 12:30:18 PM EST

(from Eileen, to Ron Efron and Minerva)

Suze just got back to me - she really sincerely wants

to come Sun. evening, but she has “not been well”

(sounds serious). She told me to tell you both.

Suze missed the opening reception for Stephanie’s memorial show, but I hoped that she could see the show before it came down. I left a few messages on her phone. Enzo finally called to tell me that she was too sick to visit the studio.

Suze Rotolo died of lung cancer at her home on February 25, 2011, aged 67, in Enzo’s arms, we were told.

NOTE: To see scores of Susan Rotolo’s handmade books online go to Medialia Gallery’s website:

http://www.medialiagallery.com/artists/Rotolo/Rotolo.html

copyright © 2016 Minerva Durham

index

index